“Neal wants a full cost per pound of hunting venison analysis. He swears it’s more expensive than buying in the store. Please post on my page so he can see it.”

After an initial chuckle, I decided that this was a good exercise. Not only does it appeal to the engineer in me, but it’s a handy thing of which to keep track. I have always believed that overall the cost of hunting venison was, worst case, comparable to purchasing beef; and I suspected that it was most likely less. However, I have never sat down and worked up a comparison. My response is way too long and detailed to post directly on my cousin’s FaceBook wall, and to be honest, this is really good blog fodder. I am not sure what Neal is expecting to see, but I doubt this is it.

Background

I am pro-hunting. When I was a kid, I remember Daddy and Mom stringing up the deer he had hunted from the grapevine trellis off the back deck and doing their own butchering. No meat went to waste and I seem to recall most of the bones ending up in the stew pot to make broth, which Mom froze for later use as soup stock. We ate a lot of rabbit when I was a kid too. Mom has an incredible BBQ Rabbit recipe.

Fast forward to today, my hubby and father-in-law hunt. It consumes their fall and early winter free-time. Everything is planned around it. It’s something they enjoy doing together and it’s great recreation. I have always encouraged Hubby to hunt because he enjoys it so much and because I believe that this kind of father/son time is priceless, regardless of age. At some point in the future, when my kids are old enough, I hope that my hubby and father-in-law will teach them to hunt as well for the same reasons.

The wild game we harvest never goes to waste. Our freezer is not just filled with venison, but also pheasant, duck, and goose. Because Hubby keeps us supplied with wild game, I really don’t buy much in the way of meat from the store, just the occasional pound of bacon or picnic ham to satisfy a pork craving and fish. If a recipe calls for beef, I substitute venison or, sometimes, goose. If it calls for chicken, I use pheasant. For this reason, I classify the expenses associated with Hubby’s hunting under ‘Groceries’ instead of ‘Recreation’ in our family budget.

Other Considerations

There are numerous benefits to eating wild game. It’s not treated with synthetic hormones, questionable antibiotics, nitrates/nitrites, questionable preservatives, or artificial ‘flavor enhancers’. This appeals to me from an organic living standpoint. Nutritionally, it’s very hard to compete with venison and most wild game in general. Per several studies referenced in the September 2000 Deer & Deer Hunting article, "How Healthy is Venison?” (read a reprinted copy here), a 3½ ounce portion of lean ground beef has 31% more calories, 189% more fat, and 118% more cholesterol than an equal portion of venison. Venison also wins hands down in a vitamin and minerals comparison. You don’t have to take my word for it, go the USDA National Nutrient Database and check out the comparisons for yourself. From a health care cost point of view good nutrition has significant monetary value; however, for purposes of this analysis, I have not attempted to quantify it.

Hunting also has advantages in controlling the deer population. We live in Iowa where the food supply for deer is virtually limitless. Because they have so much to eat, the average whitetail doe has two, sometimes three, fawns per year here. Humans have destroyed the natural predator populations and taken over huge acreages of habitat. Without hunting, the only things to keep deer populations in check are Lyme disease, chronic wasting disease, and deer/vehicle collisions; all of these being excruciating ways to die. I shudder to think how the deer population would explode if hunting were not allowed. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) makes deer population and harvest numbers publicly available for anyone who is interested. I am not going to spend a lot of time on the importance that harvesting deer plays in terms of public safety and preventing property damage. These benefits have tangible monetary value; but, I am not considering them for purposes of this article. Perhaps, I’ll do a follow-up article at a later date.

I think it's worthwhile to mention that all of the revenue generated by hunting license fees in Iowa goes into a constitutionally protected Fish and Wildlife Trust Fund. This fund is pays for the majority of the IDNR's fish and wildlife management activities including restoration of native habitat, planting food plots, managing wetlands, acquiring additional land for hunting and fishing, paying for lake improvements and access, and law enforcement activities. Thus, these functions are not paid for with tax payer dollars.

I also think that Iowa's Help Us Stop Hunger (HUSH) program is worth mentioning. It is cooperative effort among deer hunters, the Food Bank of Iowa, meat lockers, and the IDNR. It functions to control the deer population while providing red meat to the needy. The program is funded by a $1 surcharge included in the cost of the deer license. A hunter can donate any legally taken deer of any sex from any season by dropping it off at a participating meat locker, where it is processed, and then transported to the Iowa Food Bank for distribution. During the 2009 alone, more than 7,075 deer were donated to HUSH, generating 1.2 million meals to Iowa's less fortunate.

Harvested Meat Yield

According to IDNR, the typical Iowa whitetail buck ranges between 240 and 265 pounds on the hoof. The typical doe ranges between 140 and 160 pounds. For purposes of this analysis, I used an average buck live weight of 252.5 pounds and an average doe live weight of 150 pounds. The method for estimating realistic meat yield based on live weight is outlined on the Butcher & Packer website. This method condenses down into a single equation: Realistic Meat Yield = 0.2753*Live Weight. Thus, each buck yields 69.5 lbs meat and each doe 41.3 pounds of meat on average. Hubby routinely harvests three deer each year, one buck and two does for an average total of 152.1 lbs of meat, in an assortment cuts.

Capital Investment in Equipment

Most hunters invest in a certain minimum amount of equipment. While it is possible for the occasional hunter to borrow some of this equipment, anyone who hunts routinely should really get his own. Because we live in Iowa, deer season is cold, often with snow on the ground; thus, I have included a good pair of boots and winter wear in this list. My hubby uses this gear for snow blowing the driveway, sledding with the kids, and working outside when it’s cold. So really, this was an investment we would have made regardless; however, for the sake of conservatism, I have included it in the cost of venison. The table below provides an itemized capital equipment list, cost of new equipment, life expectancy, salvage value (if any), and annual straight-line depreciated cost.

Just as a side note for those unfamiliar with deer hunting regulations in Iowa, rifles are not permitted except occasionally during a limited season in one or two of the southern counties. Hunters here use shotguns fitted with slug barrels. There is also a bow season. However, Hubby doesn’t bow hunt so I did not figure those costs into this analysis. Handy capital items not included, because we would own them regardless, are a chest freezer and a pick-up truck.

Please note that the annualized cost of the shot gun shown here is an overestimate for anyone who uses that weapon to hunt anything in addition to deer (e.g. pheasant, goose, duck, and turkey). You would have to account for the total pounds of meat hunted with the gun to make the adjustment. So realistically, for us, the final cost per pound of venison number generated here is a bit high.

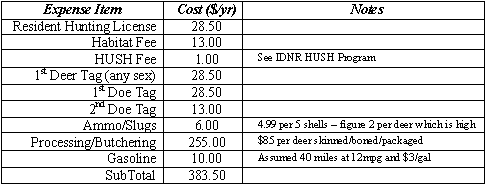

Annual Expenses

The annual expenses associated with deer hunting in Iowa are itemized in the following table.

We have our deer butchered and processed at Ruzicka’s, a meat locker in nearby Solon, Iowa. However, you could save the majority of your annual operating expenses by doing the butchering yourself, as my parents did when I was a kid.

Cost Comparison: Our Hunted Venison to Store Bought Beef

Thus, the total annual expense of hunting venison in Iowa is $428.08 with a 152.1 pound meat yield which comes to $2.81 per pound venison, regardless of cut (i.e., everything including steaks, roasts, chops, tenderloin, and ground).

So how does this compare to the current price of beef in the store? (For the sake of argument, I am going to ignore how government subsidies and price supports create an artificially low price for beef.) The most realistic comparison would be with organic grass-fed beef, which brings a premium in most stores. However, not surprising to me, our hunted venison also bests the prices for the cheaper commercially raised and processed beef as well. I compared prices from three different sources – the USDA Economic Research Service, Hy-Vee (an Iowa based grocery chain), and New Pioneer Coop (our local whole foods store).

Hands down the best nutrition for the best price is our hunted venison. My hubby does a great job bringing home the groceries!